Trying to grow a business can seem impossible. Some marketing works, other campaigns just get lost in the shuffle. Most of the time, the increased business from a campaign disappears just as quickly as it arrived. Instead of wasting your budget on promotions, you need to focus on one of the three engines of growth. When you do, you’ll build sustainable growth that will drive your business forward.

Before I jump into explaining how you can build sustainable growth, I need to give credit where credit is due. A couple of months ago, Eric Ries released a book called The Lean Startup. This is one of the most critical books to read as a business owner. These concepts are straight from his book so if you want to get an in-depth explanation, definitely pick it up.

The 4 Ways Customers Drive Sustainable Growth

1. Word of Mouth -When people love your product, they’ll tell other people about it. Great word of mouth is often the Holy Grail of advertising. It’s cheap, incredibly effective, but also difficult to build deliberately.

2. A Side Effect of Using the Product – Many products advertise themselves. iPhones, Coach purses, and Gmail are great examples. Simply by using a product, a customer advertises your product to people around them.

3. Paid Advertising – This is what most businesses rely on. As long as you’re able to keep the cost of advertising below your marginal revenue from the campaign, you’ll do just fine. Businesses run into problems when they don’t keep advertising costs under control. To help you do this, make sure you’ve built a system that can track the effectiveness of the ads (Google Analytics, coupon codes, etc).

4. Repeat Use – Many products need to be bought repeatably in order to continue to use them. Magazine subscriptions, supplements, Netflix, and web hosting are all examples of this. When you have a product that requires repeated purchases, you only have to obtain a small number of new customers to keep growing.

Now that we’ve covered the ways customers build a sustainable business model, what are the three engines of growth that you should focus on?

The Sticky Engine of Growth

If you’re focused on retaining customers for the long term, this is the engine you need to focus on. Maintaining a low customer attrition is absolutely critical. You need to do everything you can to keep your customers coming back month after month. Once you have an exceptionally low attrition rate, you only need to acquire a few new customers to keep your business growing.

Before focusing on finding new customers, focus on your current ones.

The Viral Engine of Growth

This is the domain of word of mouth and having your product advertise itself. Either by telling their friends or simply using your product, your customers will do your advertising for you.

The most critical element of this engine is making sure the every customer brings more than one friend to your business. If 10 of your customers bring 11 of their friends to you, your business will grow rapidly. Because those 11 will bring 11 (or 12) of their friends. Every group will be bigger than the last an you’ll get compounding growth.

Be careful about relying on this engine of growth, it’s incredibly difficult to build intentionally. For you to rely on viral marketing, your product needs to be absolutely incredible and fit your target market perfectly. If everything isn’t perfect, the viral loop will hit a dead end and you’ll run out of customers without other marketing.

The Paid Engine of Growth

This is what most business owners are familiar with and every form of advertising falls into this category. Whether you’re using the yellow pages or Super Bowel ads, you’re buying your customers.

When operating on this engine, each customer needs to give you a profit. If you’re spending a $1.00 to acquire a customer, you better be making enough to cover the $1.00, your other expenses, and leave a bit of profit left over. As long as you’re making a profit on each customer, you can invest those profits into more advertising to accelerate growth. Purchasing ads, employing sales teams, and leasing expensive real estate for foot traffic are all examples of the paid engine of growth.

Make sure your costs are covered.

Can you use more than one engine of growth?

You can and many businesses do, especially larger corporations. But as a small business owner, it’s much better to focus on one engine at a time. If you’re trying to go viral, make your product sticky, and pay for customers, it’s going to get very difficult to figure out what’s working.

Flaws in the Engines of Growth Model

The third system of growth (The Sticky Engine of Growth) really isn’t a system of growth.

This applies to two types of businesses, subscriptions and user engagement. Software-as-a-Service companies use subscriptions so the longer people stay subscribed, the more money they make. For consumer tech companies like Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook, they rely on user engagement so they can monetize their users with ads. In both cases, the business benefits as users keep using the product over the long term.

The strategy for this growth engine is pretty straightforward: reduce your churn to increase the value of your customers. You do this by keeping customers engaged and lowering the percentage that leave in any given month (your churn rate).

But Ries’ Sticky Engine of Growth doesn’t actually produce growth that scales.

You Can’t Get Hockey Stick Growth By Only Attacking Churn

Churn is not a path to growth. It simply raises your growth limit. It’s the ceiling that lets you keep playing. It buys you time and gives you more breathing room.

But if you want hockey-stick growth, you’ll need to build another engine of growth WHILE attacking your churn rate.

Here’s the problem: when you have a “sticky” business and need long-term customer engagement, churn puts your business into a constant rate of decay.

Churn nips at your heels, rots your customer base, and will deadweight your company if you’re not careful.

Let’s do a quick example.

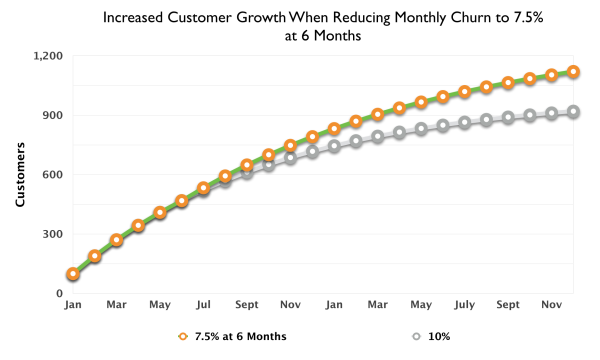

Say you have a 10% churn rate for a SaaS app. Let’s also say that you’ve found a way to acquire 100 customers per month. Here’s what happens to your growth if you keep your acquisition constant:

Early on, the 10% churn doesn’t really matter. Your 100 new customers easily make up for it. But once you get to 1000 customers, you churn rate equals your acquisition rate. Within 2 years, your business has stalled.

In order to beat churn, you have to keep accelerating your growth. Even if you have 1-2% churn (the goal for SaaS companies), your growth will consistently slow down unless you build another engine to accelerate it. Churn doesn’t get you to the next level, it simply let’s you take another shot.

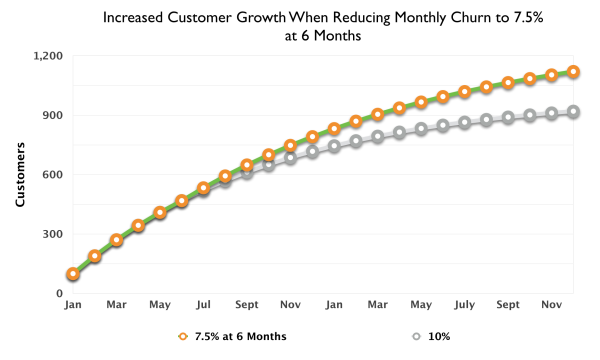

Now let’s say that we reduce the churn rate from 10% to 7.5% after 6 months. Here’s how your growth differs from the first example:

See how you hit that next ceiling after an small spike? When people talk about growth from lower churn, it’s that initial spike since the growth rate now exceeds the churn rate. But it doesn’t take long for the new churn rate to catch up and stall the business again.

No matter how low you get your churn, you’ll hit a cap sooner or later. Your growth will keep slowing down as every month goes by. The only way to accelerate growth is to build one of the primary growth engines: organic or paid.

The reason that churn is so nasty is that it quickly scales to the size of your business. 10% churn with 100 customers means that 10 customers left this month. If you somehow manage to get to 100,000 customers without addressing your churn, you’ll now be losing 10,000 customers each month. It’s fairly consistent all the way up. But marketing, sales, and growth systems don’t scale so easily. Paying for 10,000 new customers each month is an entirely different game than 10 new customers. Even viral systems don’t scale forever, they’ll start to slow and churn will catch up in a hurry.

And don’t convince yourself that you can achieve some absorb churn rate like 0.1%. Top-tier SaaS businesses are in the 1-2% range, maybe as low as 0.75%. There are hard limits on how low you can go.

Considering that most VC’s are looking for at least 100% year-over-year revenue growth rates for SaaS (consumer tech has even more absurd growth benchmarks), you need to build a growth engine that doesn’t mess around.

I’ve spent over 4 years understanding the growth model of a SaaS business at KISSmetrics, then worked at other companies with their own subscription products. While churn is a top priority, we wouldn’t get very far unless we committed to building an additional growth engine for every subscription product. That’s why we built out our marketing and sales teams.

Maybe you double-down on product and customer service to accelerate word-of-mouth. If you’re in consumer tech, a viral invite system might work if it adds to the core value of your product. Or maybe you build a paid engine with content marketing and ad buys. Either engine can work. But you need to remember that growth won’t come just from lower churn.

Why does this matter?

If you’re building a business that relies on keeping customers engaged over time, you cannot expect to grow your company from just a low churn rate.

Churn is absolutely CRITICAL to the success of your business. But it’s only one piece of the puzzle.

Look at any SaaS business that has IPO’d recently like Marketo or Box. They all have massive marketing/sales budgets. They’re even hemorrhaging cash to keep accelerating their growth rates.

That being said, I DO agree with Ries that the primary goal of a sticky business model is to focus on customer retention. No subscription or engagement business is going to get very far unless they control their churn. You’ll hit a ceiling that won’t budge until you do. Before you can think about growth, you need to get your churn to acceptable levels. Or all your customers will leave just as fast as you acquired them.

But once you have a low churn rate, growth isn’t going to magically appear. And a business looking for high rates of growth will need to acquire customers at scale. Raising engagement will increase the value of your current customers but it won’t necessarily bring you new customers. You’ll need to delight customers to the point that word-of-mouth and virality start working in your favor. Or you’ll need to start paying for customers.

Sticky Engines Don’t Acquire Customers, They Grow Customer Value

The primary benefit of sticky engines isn’t growth, it’s an increase in customer value.

Any subscription or engagement business attempts to spread customer payments out over a long period of time. For many SaaS businesses, the goal is to keep customers subscribed for 24-36 months. By spreading payments out, you’re able to increase the value of your average customer. This is one of the main reasons that tech companies have moved to subscription payments instead of up-front software licenses. And consumer tech companies can monetize long-term, active users a lot easier with ad revenue.

In fact, a well-executed upsell and churn reduction system can give you negative churn. This means the value of your current customers is increasing faster than the value lost from customers leaving. Your total customer count drops while your revenue increases slightly. Even if you don’t acquire any more customers, your revenue will still grow. At least in the short-term.

But this isn’t considered a primary growth engine. It’s mainly a strategy to mitigate the impact of churn so you get the full benefit of your real growth engine. The revenue growth from negative churn pales in comparison to any half-decent growth engine. Negative churn will only give you marginal gains.

Won’t Better Engagement Lead to More Word-of-Mouth and Virality?

Possibly.

Word-of-mouth growth requires a level of engagement well beyond what it takes just to keep customers engaged each month. Providing enough value to keep customers interested is one thing, providing enough for them to drag their friends into the product is something else altogether.

If you’re pursuing organic growth instead of paid, many of the tactics you employ will be very similar to the tactics that you’d use to reduce churn:

- Improve value of product

- Reduce friction across all customer touch-points

- Focus on a single market

- Provide fast and helpful customer service

But you’ll need to perfect these tactics and delight your customers at a level well beyond what it takes just to reduce your churn. At that point, you’re deliberately pursuing an organic engine of growth.

Eric Reis (Kinda) Disagrees With Me

Eric Ries even responded to this post (which was awesome) with 4 tweets:

@__tosh @LarsLofgren couple disagreements: 1) viral growth is special, where invites happen as a necessary side effect of product usage

— Eric Ries (@ericries) April 11, 2014

@__tosh @LarsLofgren 2) your analysis of churn presupposes that WoM is constant, but it’s not: it is proportional to size of customer base

— Eric Ries (@ericries) April 11, 2014

@__tosh @LarsLofgren 3) I never said that churn produces growth. Sticky growth compounds if WoM > churn.

— Eric Ries (@ericries) April 11, 2014

@__tosh @LarsLofgren 4) lumping different forms of acquisition into the “organic” bucket is a mistake I see hurt a lot of startups

— Eric Ries (@ericries) April 11, 2014

Two bits of nuance that are worth expanding on here.

Error #1: Blending Word of Mouth and Viral Engines

Eric Ries clearly separates viral from word-of-mouth (organic) engines of growth. I incorrectly lumped them together. In the first paragraph of his section on viral engines of growth, Ries states:

“This is distinct from the simple word-of-mouth growth discussed above [the sticky engine of growth]. Instead, products that exhibit viral growth depend on person-to-person transmission as a necessary consequence of normal product use. Customers are not intentionally acting as evangelists; they are not necessarily trying to spread the word about the product. Growth happens automatically as a side effect of customers using the product.”

Page 212 of The Lean Startup if you’re curious.

Fair enough, viral and word-of-mouth engines aren’t the same. One depends on delighting customers to the point where they voluntarily tell others about you. Viral engines depend on making the product visible to others as each customer uses it.

Keeping viral and word-of-mouth engines separate makes a lot of sense.

That’ll teach me to build off of frameworks while skimming them instead of reading the entire chapter again.

My bad.

Error #2: Ommiting that the Sticky Engine Scales When Word-of-Mouth Exceeds Churn

Eric Ries focuses pretty heavily on getting retention as high as possible for the sticky engine of growth. Page 212 in the Lean Startup:

“[For an engagement business] its focus needs to be on improving customer retention. This goes against the standard intuition in that if a company lacks growth, it should invest more in sales and marketing.”

In my post, I showed that growth hits a ceiling no matter how low you get your churn. This is because churn will eventually match your current acquisition rate. Even if you lower churn, your growth looks like this:

There’s one main exception to this.

When you get a word-of-mouth growth rate to exceed your churn rate, you’ll grow exponentially. Even though your churn grows each month, so does your word-of-mouth. Then you get a nice compounding growth rate that accelerates over time. Ries points this out on page 211:

“The rules that govern the sticky engine of growth are pretty simple: if the rate of new customer acquisition exceeds the churn rate, the product will grow.”

But this doesn’t change my primary point: churn is not the key to growth for the sticky engine. Accelerating word-of-mouth is the key instead of churn. Getting customers to keep using your product is one thing. Getting them to put their own reputation on the line by recommending you is another hurdle entirely. You’ll still hit low churn long before you see any substantial word-of-mouth.

Ries does bring up an example of a business that has 40% churn and 40% acquisition at the same time. And when your churn matches your acquisition, you stall. He focuses on lowering churn to get the sticky engine running. But I’m skeptical that the acquisition is coming from actual word-of-mouth. With churn that high, I’d expect the acquisition to be from conventional sales and marketing channels that don’t scale with churn. And if that’s the case, lowering churn is only the first step. You’ll hit a new ceiling since your acquisition won’t scale as easily as churn does.

If you have worked with a business that achieved high rates of growth from word-of-mouth but also had high rates of churn, I’d love to hear about it. Be sure to let me know in the comments.

Once again, churn is just one piece of the puzzle. You’ll still need to keep refining your product and improving your customer support long after you achieve low churn. Word-of-mouth requires delighting customers at an entirely different level than what it takes to keep them around. In other words, low churn is the first step to word-of-mouth growth. It grows your average customer value and extends your runway. But you’ll need to keep pushing in order to get your word-of-mouth high enough that it outpaces churn. Then, and only then, will you have a sticky growth engine.

If you focus on delighting customers to the point where you get a sizable amount of word-of-mouth growth, you’ll hit low churn along the way.

To recap, you have two options when your growth stalls:

- Find a way to accelerate your current acquisition with paid or viral engines (you’ll eventually hit another plateau unless you keep accelerating it)

- Focus on your product and customer support to increase word-of-mouth (and lower churn along the way).

Lowing your churn will make either strategy more viable. You’ll either start growing exponentially at a lower rate of word-of-mouth or you’ll lower the demands on your acquisition which makes it easier to outpace churn.